The Snowy River Bandit

The main article first appeared in

Gippsland Heritage Journal

#28 (2004).

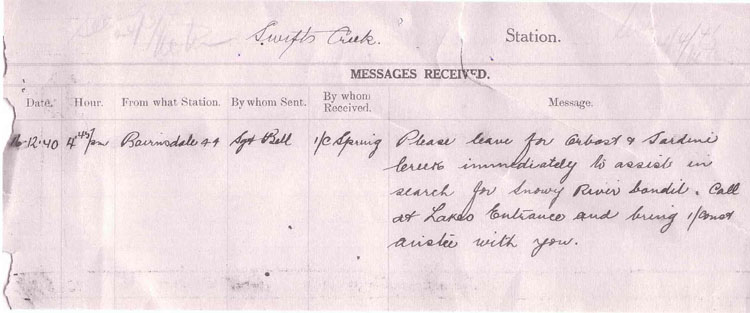

This brief message is an entry from the leather-bound tome that was the Swifts Creek Police Station Telephone Message Book, torn from the book as it was being dispatched to the incinerator. Sadly, the unthinking destruction of irreplaceable police documents was standard practice for decades and is the main reason why so few Gippsland police records exist: this page surviving only because of its intriguing reference to the Snowy River Bandit. But just as this message sparked First Constables Len Anstee and John Spring on their hunt for the bandit in 1940, so too did it start the search afresh in 2000, when armed with only the torn page and an historian’s fascination, the author picked up the trail of the eponymously named bandit, who proved as elusive in history as he was in banditry. 1 For a time the trail remained cold. A literature search of the usual Gippsland references and major libraries revealed nothing and most of the people who might have been informative oral sources were dead or of whereabouts unknown. As is increasingly the case in the age of the computer it fell to the internet to provide the first clues and these initially proved fascinating and whetted the historian’s appetite for more. One of only two internet sources to mention the bandit, clearly adhering to the adage that the facts should never get in the way of a good story, described the Snowy River Bandit thus:

The second internet source in similar vein expanded on this information and added:

It made for interesting reading but neither source identified the Snowy River Bandit and further research would show that the only verifiable facts in both articles was the bandit’s sobriquet and the reference to a gunfight. So who was the Snowy River Bandit and what was the nature of his banditry? Despite claims that the Snowy River Bandit ‘was much admired by the common folk’ and that he ranged on horseback between the Snowy Mountains and Lakes Entrance, the first newspaper reference to him less glamorously dubbed him the ‘Butcher’s Ridge food bandit’ and a notice in the Victoria Police Gazette nondescriptly described him as:

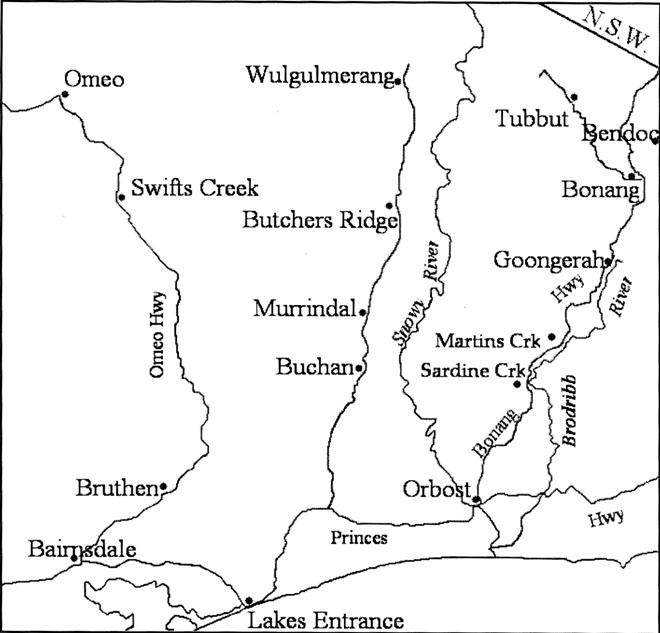

At 9.15 am on Tuesday 26 November 1940, armed with a double-barrelled shotgun, he robbed Miss Daisy Westphal and her sister Mrs. F. Stokes in their isolated home at Butcher’s Ridge, north of Buchan. The two women were home alone when the bandit ordered them from the house at gunpoint and stole a quantity of food. They were shaken but unharmed and fled to the Butcher’s Ridge Post Office where they raised the alarm. Mounted police from Bruthen, Buchan, Omeo, Orbost and Lakes Entrance, under the command of Inspector H. J. Carey of Bairnsdale, assisted by Detective John Webb of Sale, searched the Murrindal and Wulgulmerang areas for almost a week but the bandit vanished without trace: ‘not even a footprint’ was found. Much of the search area was described as ‘impenetrable jungle’ and one local resident observed, ‘you could ride a horse almost on top of him and not see him’. Inspector Carey later prematurely opined to a newspaper reporter:

The bandit had escaped but not into New South Wales. On Monday 2 December 1940 a man fitting the bandit’s description stole boots and foodstuff from a camp at Tubbut. ‘Well accustomed to the bush’, he eluded a search by police from Bendoc and Orbost, leaving behind ‘a discarded pair of boots with little of the leather soles left’. Three days later he raided another bush camp at Goongerah, stealing tobacco and food. Still described in the Victoria Police Gazette as ‘A man, name unknown’, police added to their description of him that he was of ‘athletic build … carrying a large unrolled swag’. And just to demonize him slightly in the parlance of the times, his toothbrush moustache was changed to a ‘Hitler moustache’. Again the police thought that ‘he was making for New South Wales’. 6 On Thursday 5 December 1940, Jim Leatham and a friend were mustering cattle on the Bonang Highway between Goongerah and Sardine Creek when they encountered the bandit, who was carrying two rifles. The bandit did not speak to them but intimidatingly loaded one of the rifles before they left on horseback and reported the incident to the police at Orbost. The only telephone link between Orbost and Bonang was via Sydney and it was not until the following day that police reached the location of the Leatham incident. Just minutes before police arrived at the scene, the bandit, who had been lying in ambush, fired a shot at Clarence Sutton, an elderly local resident who was walking along the roadway; apparently in the mistaken belief that Sutton was searching for him. This incident caused the Argus to declare the bandit an ‘Armed Maniac’: a notion given some credence when the bandit stopped a cyclist on the roadway to ask, ‘how the Government was going in Canberra’. Searching police were of the erroneous view that, ‘the man is probably a former gold prospector, which would account for his knowledge of the bush’ and although the bandit ‘was making toward Orbost’; police again thought ‘he might turn back into New South Wales’. 7 Perhaps it was wishful thinking on the part of the police that the bandit might head north and go interstate but he didn’t. He vanished into ‘jungle country off the Bonang Highway’ for several days and continued heading south toward Orbost, emerging at Martin’s Creek on Thursday 12 December 1940, where he robbed a Country Roads Board worker. Robert William ‘Bill’ Sedan was breakfasting when a face appeared at the window of his hut. ‘Clean shaven except for a Hitler moustache’, the stranger was armed with two rifles. Pointing them at Sedan, he ordered him from the hut, then stole food and binoculars, together with a firearm that he cut down at the hut using a hacksaw to make a sawn-off shotgun. Sedan fled on foot and was eventually picked-up by a transport driver who took him to the Orbost Police Station to raise the alarm. 8

Now convinced that the bandit was not heading interstate, East Gippsland police escalated their search and were joined by police from Delegate in New South Wales and a motor cycle patrol unit, Queensland black tracker and finger print expert from Melbourne. Fifteen ‘heavily armed’ police were assisted in their search by several drovers and experienced bushmen. They concentrated on patrolling roads at night, which was when they believed that the bandit was on the move and on watching isolated farm houses and huts that they felt were his most likely targets. A lack of telephones and police radios made efficient communication almost impossible and the night time vigils lonely. Newspaper reports described it as arduous work, undertaken in stifling heat and humidity and Every Week noted, ‘To feed the police fifteen large loaves of bread were included in a two days ration’. 9 While the police ate bread the bandit celebrated his twenty-ninth birthday with rhubarb pie: which is what he stole after exchanging shots with a Sardine Creek resident on 16 December 1940. After the robbery at Sedan’s hut the bandit again vanished into thick bush for several days, emerging from the cover of jungle country at Donchi’s hut near Sardine Creek. He was seen by Jean and Alice Godber at the hut after all ‘the men folk had left for work’ and was surprised when Ted Godber returned home and fired a rifle at him. The two men then exchanged shots with the bandit allegedly dropping on one knee and taking aim at the two women, one of whom was carrying a baby. No one was wounded and as was his modus operandi, the bandit stole food before fleeing on foot into the bush. This encounter moved police to advise local settlers to arm themselves and to ‘shoot on sight if threatened’. 10 This time it wasn’t long before the Queensland black tracker was on the bandit’s trail and he followed him for six miles, losing the trail only when the bandit crossed the Brodribb River and walked along river rocks. Police regarded the bandit as an astute bushman and were aware that to confuse them he backtracked over his own trail and kept crossing the Bonang Highway. However, on Friday 20 December 1940, his bush craft failed him when smoke from a fire he had lit to cook porridge in a jam tin was seen by three Forestry Commission workers. They watched from a thicket as the bandit carrying three firearms emerged from a hollow log in which he had been hiding. One of the workers, E. Downing, rode his bicycle to a nearby road worker’s hut in which First Constable John Spring of Swifts Creek and First Constable J. Morrison of Stratford had been laying in wait for the bandit for three days. When the police returned to the scene of the sighting with Downing, the bandit initially challenged them ‘to come in and get me’ but when Morrison fired two warning shots near his head the bandit dropped his rifle and surrendered. It was later discovered that the bandit had a gunshot wound to the shoulder and powder burns on his forehead; which police alleged were self-inflicted. 11 Following his arrest the bandit was transported to Orbost, where he was charged with shooting with intent to murder, robbery and related offences. Dr Nettleton of Orbost examined the bandit and directed that he be transferred to the Bairnsdale District Hospital, where he was admitted and placed under police guard. On 2 January 1941, ‘Looking pale and dejected’ but ‘well groomed’ and wearing a ‘new navy suit’ he appeared before Mr. H. J. Towner in the Bairnsdale Court and was remanded in custody to appear at the City Court in Melbourne on 10 July 1941. 12

Alan Torney's thumb print on the police fingerprint form. (A copy is held by the author) Arrested as Alan Torney, the bandit was fingerprinted on 2 January 1941 and apart from several cryptic Victoria Police Gazette references, that fingerprint form is the only surviving police record of his arrest: it shows his date of birth as 16 December 1911; his place of birth as Avoca, Victoria; his occupation as sleeper cutter; and his address as Eden, New South Wales. Torney reportedly told police that he had enlisted in the A.I.F. but did not go into camp, instead getting ‘lost in bush’ near Pambula in New South Wales. When found he was placed in an institution at Goulburn, New South Wales from which he escaped. He then spent months travelling through ‘wild mountain country’, sleeping in hollow logs and stealing food from huts and shooting kangaroos, rabbits and sheep to survive, until finding himself in East Gippsland, where he commenced his depredations at Butcher’s Ridge. 13 On Friday 7 February 1941, Sub-Inspector Charlesworth appeared in the City Court and advised Police Magistrate, Mr. McLean that Torney had been certified insane and requested that the charges against him be withdrawn. The application was approved and Torney was admitted to a mental hospital, from which time almost nothing about him is known. When his mother died in 1951 her probate file listed his address as Ararat. 14 There the story of the Snowy River Bandit might have ended but for his romanticized appearance in late twentieth-century accounts of Victorian bushrangers, that erroneously had him riding horses and doing daring deeds that caused the ‘common folk’ to admire him. He wasn’t the colourful, swashbuckling figure they depicted but he did exist in real life as the Snowy River Bandit: so who was Alan Torney? There is no publicly accessible official record of the personal history of Alan Torney, dating from the time of his admission to a mental hospital and details of his earlier life were clouded because the name Alan Torney was an alias. Born to Rosaline Carey nee Humphrey at Homebush Road, Avoca on 16 December 1911 his birth was registered as Allen Ernest Samuel Carey – Humphrey (father unknown). He was one of seven children and after his mother became the ‘housekeeper’ for a Samuel Torney, Allen adopted the name Alan Torney, under which name he was charged as the Snowy River Bandit. 15 This historical quest was more protracted than the original police hunt in 1940: beginning with a page torn from a thoughtlessly destroyed tome and ending years later with a birth register and fingerprint form that had both been thoughtfully preserved and archived. Tales about looting shipwrecks might have made for more fascinating reading but the challenge for historians is to write interesting history accurately and perhaps now the Snowy River Bandit has his proper place in history: not in the incinerator and minus the dynamite and horses. © 2004 - Robert Haldane Notes 1 Relatively few Gippsland police records have survived. A listing of most of those that have can be found in the Gippsland Heritage Journal, No. 6 (June 1989), pp. 37-9. Police records covering the relevant period that might have assisted with research for this article, including Watch House Books, Message Books and Duty & Occurrence Registers for the police stations at Bairnsdale, Buchan, Lakes Entrance, Orbost and Swifts Creek are all missing. 2 www.whiskerhill.dynamite.com.au/s.htm [The Dictionary of Australian Bushrangers] .This site does not appear to be online now (2010). 3 www.visitvictoria.com/display [Bushrangers]. The /display page does not appear to be online now(2010). 4 Argus, 2 December 1940, p. 2, for Butcher’s Ridge food bandit; Victoria Police Gazette, 5 December 1940, p.885. 5 Argus, 2 December 1940, p. 2, for jungle and not even a footprint; 7 December 1940, p. 1, for armed maniac; Every Week, 29 November 1940, p. 1, for Lakes Entrance reference and account of Butcher’s Ridge robbery and search; 3 December 1940, for Inspector Carey. 6 Every Week, 6 December 1940, p. 3, for Tubbut sighting; Victoria Police Gazette, 19 December 1940, p. 917, for police reports of Tubbut and Goongerah thefts and description, including Hitler moustache. 7 Argus, 7 December 1940, p. 1; 9 December 1940, p. 5; Every Week, 10 December 1940, p. 8, for Leatham and Sutton incidents, including armed maniac, cyclist and police quotations. 8 Every Week, 13 December 1940, p. 1; Argus, 14 December 1940, p. 3. 9 Argus, 10 December 1940, p. 2;14 December 1940, p. 3;16 December 1940, p. 5; 20 December 1940, p. 5; Every Week, 13 December 1940, p. 1. 10 Argus, 17 December 1940, p. 5; 18 December 1940, p. 2; Every Week, 17 December 1940, p. 1;20 December 1940, p. 1. 11 Argus, 21 December 1940, p. 5; Every Week, 24 December 1940, p. 6. 12 Bairnsdale Court Register, entry dated 2 January 1941; Every Week, 3 January 1941, p. 1; Snowy River Mail, 8 January 1941, p. 1. 13 Victoria Police Gazette, 9 January 1941, p. 19; Victoria Police Fingerprint Archives (Melbourne), Form No.70 in the name of Alan Torney, Docket No. 3278/40; Argus, 21 December 1940, p. 5. 14 Argus,8 February 1941; Snowy River Mail, 12 February 1941, p. 1. 15 Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages – Melbourne, District of Avoca, Register No. 4492 (12 February 1912). Information from Carol Judkins and Avoca Historical Society re Humphrey-Carey-Torney family history.

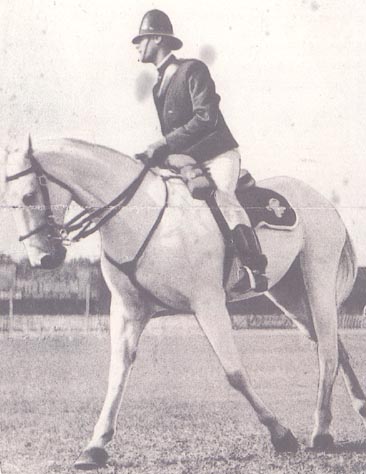

Postscript The Snowy River Bandit article previously published in the Gippsland Heritage Journal (GHJ 24:34) took several years to research and write but at the time of publication the author had not located an eyewitness or a photograph of the bandit. Following the publication of that article the author was contacted by a number of people with personal knowledge of the events, including a retired policeman, who was present during the hunt and had taken photographs of the bandit and his captors. In 1940 John Ernest ‘Jack’ Manley was a young police constable stationed at Bairnsdale, when he was directed by Sub-Inspector Henry Carey to join the hunt for ‘The Butcher’s Ridge Bandit’ near Sardine Creek, north of Orbost. Dressed in ‘outdoor civilian clothes’ and armed with his own .22 rifle, Manley’s other accoutrements included a Box Brownie camera and a length of fishing line with some hooks. ‘Tucker was in short supply’, so he used his line to catch a small eel that he grilled over an open fire: it was only marginally better than the bandit, who lived on kangaroo meat and wild nettles for weeks. Accompanied by Constable Geoffrey Chapman of Orbost, Manley was detailed to wait overnight for the bandit in an isolated road maker’s hut: they were without lighting, communications or basic provisions. It was a lonely vigil but the bandit did not arrive at their hut and was arrested closer to Orbost the next morning. During his time in the Sardine Creek area Manley used his Box Brownie camera to take a series of photographs of his police colleagues and the bandit in custody. After taking these photographs Manley was approached by a journalist from a Melbourne newspaper who did not have a camera: he asked Manley if he could have his film, with the promise that he would send him a set of the developed photographs. The journalist, who would later become famous as a war correspondent, was Osmar White: he kept his promise and Manley’s photographs survive as a unique record of the hunt for the Snowy River Bandit. Robert Haldane

Other pages on this website

This page last updated on 15 December 2014

|